History of Corn island

The Touchstone of Louisville History.

The Touchstone of Louisville History.Our name come from the historic site of Corn Island, located near the Kentucky shore on the Ohio River. Though now completely submerged in the waters, Corn Island’s history remians an important part of the region’s beginnings.

Louisville historian George Yater has called Corn Island the touchstone of Louisville’s history for its role in the founding of the city (Yater 1979:2; 2001:220). It was a small island situated near the Kentucky shore of the Ohio River above the Falls. Originally named Dunmore Island after John Murray, Crown 4th Earl of Dunmore, Crown Governor of Virginia (Wikipedia). It was renamed Corn Island by early settlers because of the first crop raised there in 1778 (Johnson and Parrish 2007:6).

The History of Corn Island

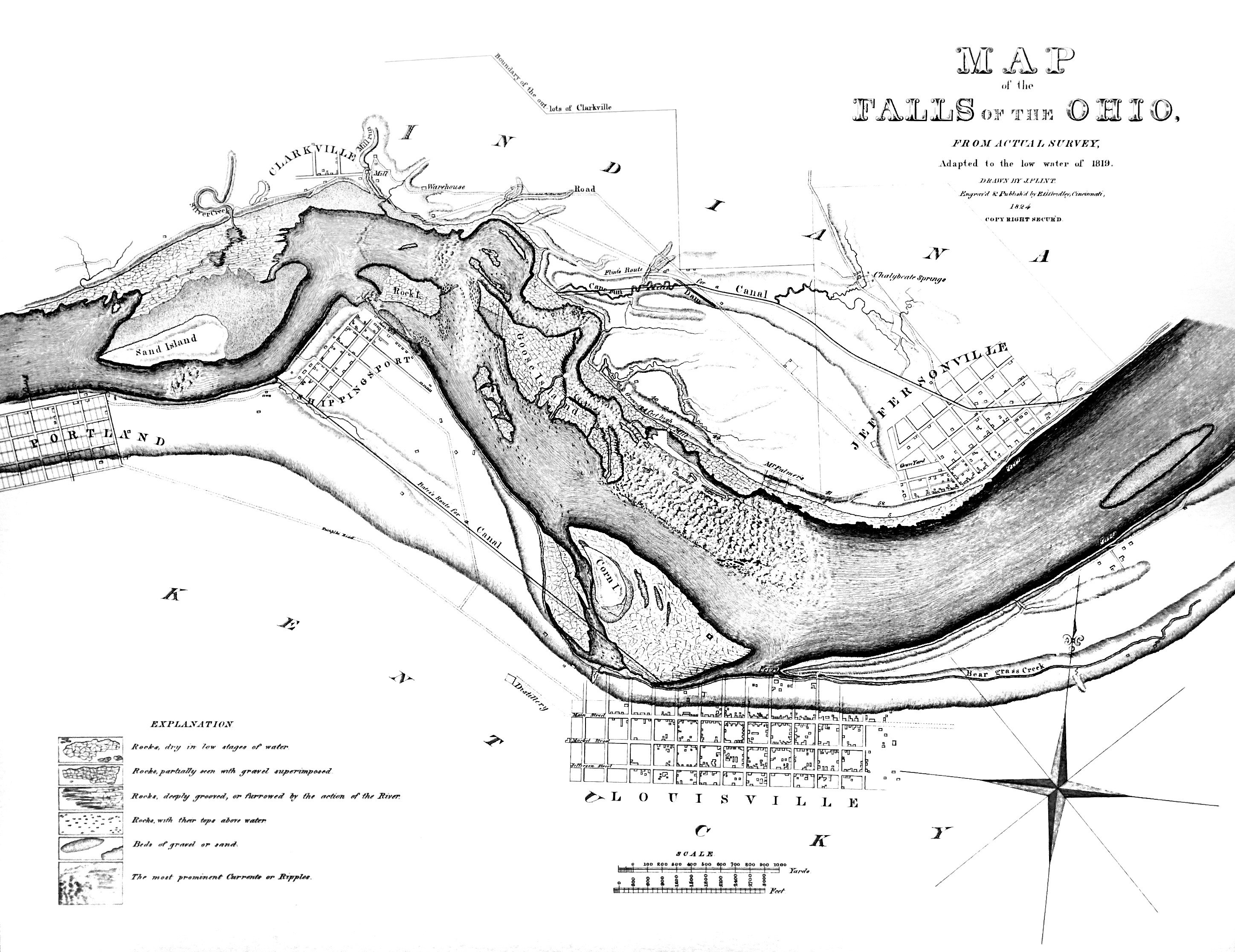

Corn Island was first surveyed by Thomas Bullitt and his party in 1773 (Wikipedia). It was mapped by Thomas Hutchins in 1766, at which time it measured 4,000 feet long and 1,000 feet wide, encompassing about seventy acres (Rave 1891). It extended along the waterfront of present-day Louisville from Fifth to Fourteenth Streets, with its southernmost point near the first river pier of the K and I Railroad Bridge. During the late 1700s, the island was covered in “great sycamores, cottonwoods, and giant cane”. At very low water, Corn Island was connected to the mainland, and in one place, it was possible to wade to shore.

The island was first inhabited by white men when General George Rogers Clark descended the Ohio River from near Fort Pitt in Pennsylvania in 1778 with perhaps ten boats and ten to twenty families. His secret orders were to capture the French-held fort of Kaskaskia in Illinois. He reluctantly allowed civilians to accompany the troops because some were related to the militia men and because the increasingly popular movement to settle Kentucky allowed a convenient cover for his real intentions. Clark had originally intended to construct a fort at the mouth of the Kentucky River and at the Falls, but since he could not adequately staff two forts, and because all boats would have to stop at the Falls, he opted to build only at the Falls (Yater 1979:3).

Clark landed his flatboats on Corn Island on May 27, 1778: “I observed the little island of about seven[ty] acres opposite to whare the Town of Lewisville now stands [,] seldom or never was intirely covered by the water, I resolved to take possession and fortify which I did” (George Rogers Clark, spring of 1778, in Yater 1979:2). A blockhouse and cabins were built. Clark intended for the island settlement to be a communications post to support his military campaign, but it is speculated that the name of the island and the nature of the civilian settlement served as a ruse for the military nature of the post (Wikipedia).

Clark chose the island for good reason: “to stop the desertion I knew would ensue on the Troops knowing their Destination [,] I had encamped on a small Island in the middle of the Falls” (Yater 1979:4). With the destination of Kaskaskia unknown to them, the troops began training as a military unit under Clark at Corn Island. When the plan was revealed, some indeed tried to desert, wading across the Ohio at low water to the mainland. They were pursued, and a few recaptured. Some perished in the wilderness. This incident and the wait for recruits, which eventually came, delayed Clark. He remained on the island for one month before departing on his campaign at Kaskaskia June 24, 1778 (Yater 1979:4-5; Wikipedia).

Clark left behind a small group of pioneering settlers and 30 militia men. An estimated 13 families of maybe 60 civilians remained in the little fort (Casseday 1852:29; Wikipedia). Among the surviving names of the families are those of Captain James Patton, Richard Chenoweth, John Tuel, William Faith, and John McManus. According to Clark, the settlers “ware of little expense, and with the Invalids would keep possession of this Little post until we should be able to Occupy the Main shore (Yater 1979:4). He most likely referred to some of the militia who were of poor health or possibly considered too old for the campaign to Illinois.

“And so, brave, hardy and resolute were these pioneers, that, notwithstanding they were separated from the nearest of the countrymen by four hundred miles of hostile country, filled with [savages] whose dearest hunting grounds they were about to occupy; notwithstanding that these relentless [savages] were not only inimical on account of the invasion of their choicest territory, but were aided by all the arts, the presents, and the favors of the British in seeking to destroy the settlements; notwithstanding all these terrifying circumstances, those dauntless pioneers went quietly to work, and with the rifle in one hand and the implements of agriculture in the other, deliberately set about planting, and actually succeeded in raising a crop of corn on their little island” (Casseday 1852:29-30).

Patrick Scott retells his father’s reminisces about the founding of Corn Island. “My father came down in 1778 with Cark’s Company. I stopped at the falls of the Ohio… They planted corn on Corn Island. Have heard my father say as he used to set of night in his cornfield, that he thought he could hear the corn to tick-tick- it grew so fast(Draper Manuscripts, 11CC5-7, in Yater 1979:6). It has been speculated that the Native Americans would never have allowed the settlers to grow sufficient food to survive for any period of time, and so the small crop was augmented by hunting. Some claim that Kentucky itself would never have been settled if the pioneers relied totally on agriculture (Casseday 1852:30). But the area around the Falls of the Ohio was rich in abundant game, both in the forests and the river.

While Clark was gone, the pioneers scouted the mainland for future homestead sites. The core group of perhaps 10-20 families was augmented by the arrival of 300 additional souls over the course of the year. The safety of the island was eventually abandoned in 1779 as the settlers moved to the mainland of Kentucky, and a charter was obtained to found the village of Louisville (Johnson and Parrish 2007:6). The “Fort on Shore” was built on the mainland opposite Corn Island, on the eastern side of large ravine which formerly entered the river at the present termination of Twelfth Street, near present day 12th and Rowan Streets. The new fort was occupied by the fall of 1778 (Casseday 1852:30-31; Yater 1979:6).

Corn Island was never settled again after 1779. It was used in a variety of manners, alternating between cornfields, woods, and industry. It was a popular spot for picnicking and fishing parties during the early to mid 1800s (Rave 1891). Many Louisville residents recalled fond memories of fish fries, duck shooting, religious festivals, and other amusements on the island. In 1824, a powder mill was built on the island; the mill exploded in 1830 (Yater 200:220). In 1850, a large farm of twenty acres was located on the fertile island (Yater 2001:220). Beginning around 1840, John Hulme and Francis McHarry, new owners of Tarascon’s Mill at Shippingport, leased a stone quarry located on Corn Island to mine limestone to grind for cement making (Johnson and Parrish 2007:72). In fact, rock may have been mined from the island as early as 1806, possibly to pave Main Street in Louisville (Yater 2001:220). With the gradual deforestation of the island, the soil washed away, and the exposed limestone was excavated to the extent that the island was in danger of being totally obliterated. In addition, the excavations caused problems for river traffic, altering the water flow above the Falls (Johnson and Parrish 2007:74; 93). During the 1850s and 1860s, Louisville historian and attorney Reuben Durrett tried to convince the city to preserve the island, but was unsuccessful (Yater 2001:220). In 1867, the first pier of a bridge over the Ohio River was emplaced on Corn Island (Johnson and Parrish 2007:123-124). By 1869, all that was left of Corn Island was a bare rock with one dead sycamore stump (Rave 1891).

In 1889, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers decided to remove the rock because it was an impediment to river traffic. Over 700 men were engaged in drilling, blasting, and removing rock to a depth of six feet. As much as 300 pounds of explosives were used daily, and the blasts shook the earth and shattered windows for miles around. The smoke generated from the “heavy engines, pounding drills, and puffing locomotives with train-loads of rock, along with the explosives, hurling and grinding of rocks” imitated a battle scene (Rave 1891).

On September 22, 1891, the Louisville Courier-Journal reported that Corn Island “will soon be wiped from the face of the earth. In another year not even the rock base above low water of the spot where General George Rogers Clark and his heroic army on their way to Kaskaskia rested will remain. Before ever-increasing needs of a growing river commerce the historic rock is blown away amid cannonading and smoke as of a great battle” (Herman Rave 1891).

“And truly so bold and heroic an act as this of that feeble band deserves a perpetuity beyond what the mere name of the island will give it. Columns have been reared and statues erected, festivals have been instituted and commemorations held of deeds far less worthy of renown than was this little settlement’s crop of corn. But like many other deeds of true heroism, it is forgotten, for there was wanted the pen and lyre to make it live forever” (Casseday 1852:29).